On a quiet Saturday morning, instead of the usual post-collection relaxation, I made my way to Oxford Brookes Headington Campus for the Oxford Premier Book Fair. This rare event brings together sellers from across the UK, offering a range of antique novels, vintage children’s books, and historical pamphlets. Held in the large hall of the Fusili building, the Book Fair quickly became a gathering place for those with a passion for second-hand books, a love deeply ingrained in Oxford’s cultural fabric.

The event’s appeal goes beyond mere nostalgia. Many, like the gentleman I overheard spending £320 in just thirty minutes, are drawn to the allure of books with a history. Oxford’s academic community, especially its older male faculty, appeared in full force, but it’s more than academic interest that drives the crowd. There’s something uniquely captivating about worn, sometimes fragile books that carry the marks of previous owners. Whether it’s a childhood memory sparked by illustrations of fairies or curiosity about gardening practices from centuries past, these books invite exploration.

Second-hand bookstores, and events like this book fair, also allow for a connection with past readers. Scribbled notes in margins or personal inscriptions—such as one that read, “Melody, Eight Years Old, February 1980″—serve as tangible links between past and present. In a bookstore in Inverness, I came across a book on Scottish nationalism with three generations of personal reflections inside. These notes formed a dialogue of hope, disappointment, and reflection over decades—an unspoken bond between people who had never met but shared a moment in time through a single book.

For me, it was the children’s books section that proved most alluring. The nostalgic pull of illustrated fantasy, especially older editions of The Hobbit, kept me engrossed. As a historian, I also found it fascinating to examine how children’s literature from past centuries subtly reinforced societal norms like imperialism, nationalism, and patriarchy. Even a collection of early 20th-century pixie illustrations conveyed underlying messages about gender and class through a seemingly innocent story about a fairy rejecting the proposal of a flower-lord.

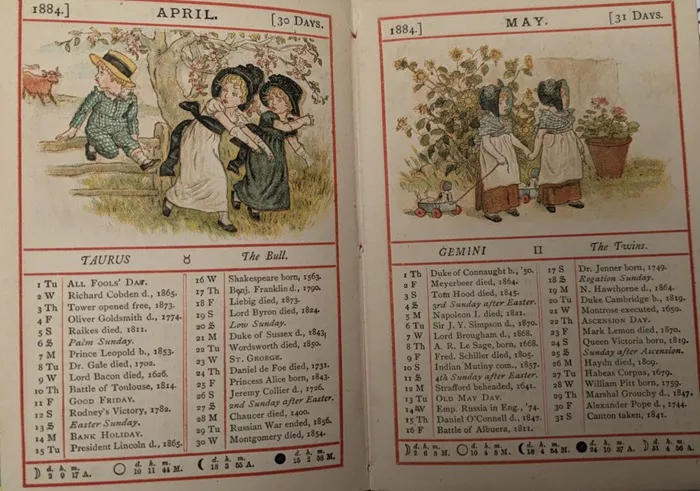

Despite my intrigue, I left the fair without making a purchase—largely due to the steep prices and my student budget. However, the experience left me with a profound sense of connection to the past, as well as a reminder of the vast, unexplored worlds within the pages of these books. While I didn’t bring home an 1884 almanac that coincidentally commemorated Charles Dickens’ death on my birthday, the fair’s sense of timelessness and the curiosity it stirred in me made the visit invaluable.