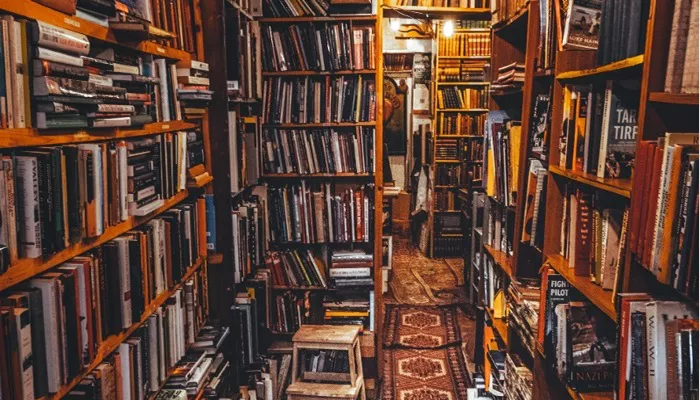

Growing up in a small resort town in the Philippines, Monica Macansantos had little access to the gleaming bookstores she would later encounter as a graduate student in the United States. Instead of polished retail spaces, her hometown offered hole-in-the-wall shops hidden in alleyways or tucked into old, unmarked buildings. These modest stores sold second-hand paperbacks with creased covers and yellowing pages, often featuring English translations of European novels printed in fuzzy, miniature text.

Macansantos’ early literary awakening came in sixth grade, when she discovered a copy of Balzac’s Old Goriot on a high shelf in her parents’ library. The book’s cover—a walled garden bathed in melancholic light—captured her imagination. Immersed in the story of Monsieur Goriot’s suffering at the hands of his selfish daughters, she lost track of her household chores. Her father, far from reproaching her, quietly took over the watering of plants, unwilling to disrupt her engagement with Balzac. Though he hadn’t read Old Goriot himself, it was likely a book he had once picked up from the public market, slipped among bags of produce and later forgotten.

For Macansantos’ father, this habit of scavenging for literary gems was deeply personal. A self-taught reader, he had worked as a janitor to pay for his first year of college. His early exposure to literature often came from the very books he was tasked with moving between floors, stealing moments to read while on the job. He borrowed, bartered, and bought cheap books, refining his command of English through the works of T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats.

Later, during a stint in the U.S., he submitted poetry to American literary journals, only to face repeated rejection. “What matters to them is language, not substance,” he would lament, attributing his lack of acceptance to the English he had learned—an English different from that of native speakers. Still, his time in the U.S. left an imprint, fostering a love for American literary culture, particularly The New Yorker. Upon returning to the Philippines, he was delighted to find an open-air stall in the public market selling decades-old issues of the magazine. Despite the age of these copies, they became a shared source of discovery between father and daughter.

Though Macansantos was just eleven at the time, her father treated her as an intellectual equal, sharing poems and stories as if she were a trusted confidante. In their world, second-hand books were not hand-me-downs but bridges to a larger literary community. “We were citizens of the world,” she recalls, “never mind if our magazines and books were all cast aside by first-world readers.”

One of her father’s favorite second-hand bookstores was housed in an aging art deco building. The shopkeeper, an elderly woman with thick glasses who later taught Macansantos how to knit, kept the radio tuned to the news as the family browsed. From this cramped space, her father unearthed eclectic treasures: a National Geographic article on Incan child sacrifices, Isak Dinesen’s Seven Gothic Tales, and even an Algebra textbook that would later help Macansantos navigate freshman math.

Among these finds was a well-worn anthology of English verse, missing its cover and barely holding together. When Macansantos began writing poetry herself, her father used this fragile book to guide her through the intricacies of language—examining each phrase, word choice, and rhythm with the care of a master craftsman.

For Macansantos, learning to write felt akin to learning to sail: a growing sensitivity to the currents and breezes of language. English, while her father’s second language, became their shared medium for expressing ideas, dreams, and emotional truths. Their literary education was predominantly shaped by white, English-speaking authors, though it also included European, Indian, Latin American, Chinese, and Japanese voices. Russian writers, in particular, left a profound impact, their explorations of human tragedy resonating with the quiet struggles of people in Macansantos’ own community.

Yet, there was a persistent absence in these narratives—the stories of people from her own corner of the world. It wasn’t until college that Macansantos deliberately turned to Filipino writers, seeking to reconcile her Westernized tastes with her cultural roots. Authors such as Kerima Polotan, F. Sionil Jose, Nick Joaquin, Antonio Enriquez, Edith L. Tiempo, and Cirilo Bautista wrote in English, yet imbued their work with a sensibility distinct from their American and British counterparts. Like her father, these writers had acquired their literary foundation through English-language education and second-hand books, using the colonizer’s tongue to engage with a global conversation that often overlooked them.

Some Filipino authors, including Wilfrido Nolledo, Erwin Castillo, and Cesar Ruiz Aquino, pushed English beyond conventional boundaries, experimenting with grammar, semantics, and narrative form to reflect the uniquely Filipino experience. Through their work, Macansantos found a new confidence in her own perspective—a worldview shaped by both her Filipino upbringing and the English language through which she had learned to articulate it.

However, her literary journey was not without challenges. During her first year in an MFA program in the U.S., Macansantos often felt the limits of her third-world literary background. Conversations with classmates casually referenced authors like Denis Johnson and Jennifer Egan—names unfamiliar to her. In these moments, she found herself nodding along in silence, pretending to recognize references that were entirely foreign.

Despite these challenges, Macansantos’ formative experiences with used books and her father’s unwavering belief in the power of language continue to shape her voice as a writer. In the worn pages of second-hand novels and magazines, she discovered not only a literary education but also a profound connection with her father and her own identity.